In the gloss provided by Gregory Nagy in H24H[1] and the associated Sourcebook[1], mēnis is summarized as “superhuman anger, cosmic sanction”.

Following the Kosmos Society Book Club discussion about Leonard Muellner’s The Anger of Achilles: Mênis in Greek Epic (available online at CHS)[3], we became interested in finding out how the word was used in other texts, so it seems appropriate to choose this for the next Core Vocab discussion.

Muellner summarized the situations in Homeric epic in which mēnis is incurred[4]:

1. disobedience of Ares to Zeus’s commands (Iliad 5.34)

2. disobedience of mortal warriors to Apollo’s prohibitions (Iliad 5.444, 16.711)

3. defiance by Achilles of Agamemnon’s authority (Iliad 1.247)

4. rape of Persephone by Hades (Hymn to Demeter 350, 410)

5. mortals having sex with goddesses (Odyssey 5.146; Hymn to Aphrodite 290)

6. leaving the dead unburied (Iliad 22.358; Odyssey 11.73)

7. desecrating a sacrifice (Iliad 5.178)

8. violating exchange rules: hospitality (Iliad 13.624; Odyssey 14.283, 2.66); treatment of beggars (Odyssey 17.14); ransom (Iliad 1.75); prize distribution (the mênis of Achilles, passim)

In the Book Club discussion we also noted that the term is not used in the Hesiodic Theogony which Muellner discusses in terms of a prooímion (‘prelude, song to precede another song’) to the Iliad, and we were interested in reading more closely The Homeric Hymn to Demeter and other texts to further our understanding of the term.

So, outside Homeric epic, to whom is the term applied? What situations incur mēnis? How closely do they fit the situations listed above? Is there a difference between male and female mēnis? And how are the related terms used in other texts?

Here are a few passages to start the conversation:

†Ζεῦ πάτερ, εἴθε γένοιτοθεοῖς θίλα τοῖς μὲν ἀλιτροῖς

ὕβριν ἁδεῖν, εἴ σφιν τοῦτο γένοιτο φίλον

θυμῷ, σχέτλια δ᾽ ἔργα μετὰ φρεσὶ θ᾽ ὅστις ἀθηρὴς

ἐργάζοιτο θεῶν μηδὲν ὀπιζόμενος,

αὐτὸν ἔπειτα πάλιν τεῖσαι κακά, μηδ᾽ ἔτ᾽ ὀπίσσω

πατρὸς ἀτασθαλίαι παισὶ γένοιντο κακόν:

παῖδές θ᾽ οἵτ᾽ ἀδίκου πατρὸς τὰ δίκαια νοεῦντες

ποιῶσιν, Κρονίδη, σὸν χόλον ἁζόμενοι,

ἐξ ἀρχῆς τὰ δίκαια μετ᾽ ἀστοῖσιν φιλέοντες,

μήτιν᾽ ὑπερβασίην ἀντιτίνειν πατέρων.

ταῦτ᾽ εἴη μακάρεσσι θεοῖς φίλα: νῦν δ᾽ ὁ μὲν ἕρδων

ἐκφεύγει, τὸ κακὸν δ᾽ ἄλλος ἔπειτα φέρει.

καὶ τοῦτ᾽, ἀθανάτων βασιλεῦ, πῶς ἐστι δίκαιον,

ἔργων ὅστις ἀνὴρ ἐκτὸς ἐὼν ἀδίκων

μήτιν᾽ ὑπερβασίην παρέχων μηδ᾽ ὅρκον ἀλιτρόν,

ἀλλὰ δίκαιος ἐών, μὴ τὰ δίκαια πάθῃ;

τίς δή κεν βροτὸς ἄλλος, ὁρῶν πρὸς τοῦτον, ἔπειτα

ἅζοιτ᾽ ἀθανάτους, καί τινα θυμὸν ἔχων,

ὁππότ᾽ ἀνὴρ ἄδικος καὶ ἀτάσθαλος, οὔτε τευ ἀνδρὸς

οὔτε τευ ἀθανάτων μῆνιν ἀλευόμενος,

ὑβρίζῃ πλούτῳ κεκορημένος, οἱ δὲ δίκαιοι

τρυχῶνται χαλεπῇ τειρόμενοι πενίῃ;†Father Zeus, I would it were the gods’ pleasure that wanton outrage [hubris] should delight the wicked if so they choose [= be philos in the thūmos], but that whosoever did acts abominable and of intent, disdainfully, with no regard for the gods, should thereafter pay penalty himself, and the ill-doing of the father become no misfortune unto the children after him; and that such children of an unrighteous [a-dikos] father as act with righteous intent, standing in awe of thy wrath [kholos], O son of Cronus, and from the beginning have loved the right [dikaios] among their fellow-townsmen, these should not pay requital for the transgression of a parent. I say, would that this were pleasure for the blessed [makar] gods; but alas, the doer escapes and another bears the misfortune [kakon] afterward. Yet how can it be rightful [dikaion], O king of the immortals, that a man that hath no part in unrighteous [a-dikoi] deeds, committing no transgression nor any perjury, but is a righteous [dikaios] man, should not fare aright [dikaia]? What other man living, or in what spirit [thūmos], seeing this man, would thereafter stand in awe of the immortals, when one unrighteous [a-dikos] and wicked that avoids not the wrath [mēnis] of man or of immortals, indulges wanton outrage [hubris] in the fulness of his wealth, whereas the righteous [dikaioi] be worn and wasted with grievous penury?

Theognis Elegiac Poems Book I: 731–752, adapted from translation by J.M. Edmonds[5]

Several words appear in this passage that further signal the mēnis, in particular being unjust [a-dikos] or acting with outrage [hubris], in particular in the eyes of the immortals, although there is also a sense of frustration that it is sometimes the next generation who suffer for the actions of their fathers, and that without immortal intervention and action there is no motivation to behave correctly.

Muellner says of Iliad 16.385–392 “the word ópis, as elsewhere, functions as a synonym of mênis“[6] and in Theogony although mēnis does not appear, this other term, ópis, does:

νὺξ δ᾽ ἔτεκεν στυγερόν τε Μόρον καὶ Κῆρα μέλαιναν

καὶ Θάνατον, τέκε δ᾽ Ὕπνον, ἔτικτε δὲ φῦλον Ὀνείρων:

δεύτερον αὖ Μῶμον καὶ Ὀιζὺν ἀλγινόεσσαν

οὔ τινι κοιμηθεῖσα θεὰ τέκε Νὺξ ἐρεβεννή,

215 Ἑσπερίδας θ᾽, ᾗς μῆλα πέρην κλυτοῦ Ὠκεανοῖο

χρύσεα καλὰ μέλουσι φέροντά τε δένδρεα καρπόν.

καὶ Μοίρας καὶ Κῆρας ἐγείνατο νηλεοποίνους,

Κλωθώ τε Λάχεσίν τε καὶ Ἄτροπον, αἵτε βροτοῖσι

γεινομένοισι διδοῦσιν ἔχειν ἀγαθόν τε κακόν τε,

220 αἵτ᾽ ἀνδρῶν τε θεῶν τε παραιβασίας ἐφέπουσιν:

οὐδέ ποτε λήγουσι θεαὶ δεινοῖο χόλοιο,

πρίν γ᾽ ἀπὸ τῷ δώωσι κακὴν ὄπιν, ὅς τις ἁμάρτῃ.

τίκτε δὲ καὶ Νέμεσιν, πῆμα θνητοῖσι βροτοῖσι,

Νὺξ ὀλοή: μετὰ τὴν δ᾽ Ἀπάτην τέκε καὶ Φιλότητα

225 Γῆράς τ᾽ οὐλόμενον, καὶ Ἔριν τέκε καρτερόθυμον.Night bore also hateful Destiny, and black Fate, and Death; she bore Sleep likewise, she bore the tribe of dreams; these did the goddess, gloomy Night bear after union with none. Next again Blame [Mōmos], and Care full-of-woes, 215 and the Hesperides, whose care are the fair golden apples beyond the famous Okeanos, and trees yielding fruit; and she produced the Destinies [Moirai], and ruthlessly punishing Fates: Klotho, Lachesis, and Atropos, who assign to men at their births to have good and evil; 220 who also pursue transgressions both of men and gods, nor do the goddesses ever cease from dread [deinos] wrath [kholos], before they have repaid sore vengeance [ópis] to him, whosoever shall have sinned. Then pernicious Night also bore Nemesis, a woe to mortal men; and after her she brought forth Fraud, and Wanton-love, 225 and mischievous Old Age, and stubborn-hearted Eris.

Hesiod Theogony 211–225, Adapted from Sourcebook

Although ópis. like mēnis, is not a personified deity as some of the other offspring of Gaia or Nyx are, the term does appear in a list of offspring that provides a context for circumstances that might be associated with cosmic anger.

Similarly in Works and Days;

οὐ μὲν γάρ τι γυναικὸς ἀνὴρ ληίζετ᾽ ἄμεινον

τῆς ἀγαθῆς, τῆς δ᾽ αὖτε κακῆς οὐ ῥίγιον ἄλλο,

δειπνολόχης: ἥτ᾽ ἄνδρα καὶ ἴφθιμόν περ ἐόντα

705 εὕει ἄτερ δαλοῖο καὶ ὠμῷ γήραϊ δῶκεν.

εὖ δ᾽ ὄπιν ἀθανάτων μακάρων πεφυλαγμένος εἶναι.

μηδὲ κασιγνήτῳ ἶσον ποιεῖσθαι ἑταῖρον:

εἰ δέ κε ποιήσῃς, μή μιν πρότερος κακὸν ἔρξῃς.

μηδὲ ψεύδεσθαι γλώσσης χάριν: εἰ δὲ σέ γ᾽ ἄρχῃ

710ἤ τι ἔπος εἰπὼν ἀποθύμιον ἠὲ καὶ ἔρξας,

δὶς τόσα τίνυσθαι μεμνημένος: εἰ δὲ σέ γ᾽ αὖτις

ἡγῆτ᾽ ἐς φιλότητα, δίκην δ᾽ ἐθέλῃσι παρασχεῖν,

δέξασθαι:There is no better possession for a man than a wife

who is good. And there is nothing worse than a bad one,

one who sneaks away the dinner for herself. The man, no matter how strong he may be,

705 is burned out by the fire of such a woman. No need for a torch! And she brings him to a raw old age.

Guard against the anger [opis] of the blessed [makar] immortals.

Do not make a comrade [hetairos] equal to a brother.

But if you do, you should not beat him to it by hurting him first.

And do not lie just to please [kharis] your tongue. But if he wrongs you first,

710 either saying or doing something that is contrary to your thūmos,

then be mindful [memnēmenos] to repay him double. But if he

takes you back into the state of being philoi, and is ready to offer dikē,

then accept him.Works and Days 702–713, adapted from Sourcebook

As with the Theognis passage, the immortal gods are referred to as “blessed” [makar]. The line “Guard against the anger [opis] of the blessed makar immortals.” seems on first reading to stand alone. But looking at what precedes and follows, are these themes of sharing food equally, having equal exchanges in strife, related to the situations that might incur mēnis?

In Athenian tragedy we might expect the poetic diction to be similar to that found in the epics. Here is one example from Sophocles:

…. ὧν ἔχων χόλον,

ὡς ἵκετ᾽ αὖθις Ἴφιτος Τιρυνθίαν

πρὸς κλιτύν, ἵππους νομάδας ἐξιχνοσκοπῶν,

τότ᾽ ἄλλοσ᾽ αὐτὸν ὄμμα, θατέρᾳ δὲ νοῦν

ἔχοντ᾽, ἀπ᾽ ἄκρας ἧκε πυργώδους πλακός.

ἔργου δ᾽ ἕκατι τοῦδε μηνίσας ἄναξ

275ὁ τῶν ἁπάντων Ζεὺς πατὴρ Ὀλύμπιος

πρατόν νιν ἐξέπεμψεν οὐδ᾽ ἠνέσχετο,

ὁθούνεκ᾽ αὐτὸν μοῦνον ἀνθρώπων δόλῳ

ἔκτεινεν: εἰ γὰρ ἐμφανῶς ἠμύνατο,

Ζεύς τἂν συνέγνω ξὺν δίκῃ χειρουμένῳ:

280ὕβριν γὰρ οὐ στέργουσιν οὐδὲ δαίμονες.Furious [kholos] at this treatment, [270] when afterward Iphitus came to the hill of Tiryns on the track of horses that had strayed, Heracles seized a moment when the man’s eyes were one place and his thoughts [noos] another, and hurled him from a towering summit. But in anger [mēniō] at that deed, the king, [275] the father of all, Olympian Zeus, sent him away to be sold, and did not tolerate that this once, he killed a man by guile [dolos]. Had he achieved his vengeance openly, Zeus would surely have pardoned him the righteous [with dikē] triumph. [280] For the gods [daimones] do not love outrage [hubris] either.

Sophocles Trachiniae. adapted from Jebb, 269–280[7]

What I noticed was that his behavior is described as hubris, going beyond the limits. And although Heracles’ anger is described as kholos the transgression is that he did not behave openly. And yet Zeus was still aware of it and punished him. However, it is interesting to look at what is said by Likhas before this episode. He recounts how Herakles was taken into slavery, and afterwards vowed to enslave the person responsible along with his wife and child.

The background to this is that although Herakles won an archery contest, Eurytus did not award him the promised prize. Eurytus’ son Iphitus was a friend of Herakles, trying to help find Eurytus’ horses which were missing, and was a guest of Herakles at Tiryns. Herakles kills Iphitus in his anger about his treatment by Eurytus, which is described just beforehand:

ὃς αὐτὸν ἐλθόντ᾽ ἐς δόμους ἐφέστιον,

ξένον παλαιὸν ὄντα, πολλὰ μὲν λόγοις

ἐπερρόθησε, πολλὰ δ᾽ ἀτηρᾷ φρενί,

265 λέγων χεροῖν μὲν ὡς ἄφυκτ᾽ ἔχων βέλη

τῶν ὧν τέκνων λείποιτο πρὸς τόξου κρίσιν,

φωνεῖ δὲ δοῦλος ἀνδρὸς ὡς ἐλευθέρου

ῥαίοιτο: δείπνοις δ᾽ ἡνίκ᾽ ἦν ᾠνωμένος,

ἔρριψεν ἐκτὸς αὐτόν.when Heracles, a guest-friend [xeinos] of long standing, came to his house and hearth, Eurytus roared against him with insults of ruinous intent [phrēn], [265] saying that, although Heracles had inevitable shafts in his hands, he fell short of his own sons in the contest [krisis] of the bow. Next he shouted that Heracles was a freeman’s slave, a broken hulk, and then at a banquet, when his guest was full of wine, he tossed him from his home.

Sophocles Trachiniae adapted from Jebb, 263–269

So Eurytus has violated at least two of the criteria listed by Muellner: he has not fairly shared a prize, and has behaved insultingly in his role as host. But then Herakles himself behaves as if he is the agent of sanction and takes his anger out on someone else, Iphitus. But such sanctions are not his to make, and he himself breaches the rules of hospitality, so the pattern seems similar to some of the issues related to how it is the gods’ role, and if a mortal hero (even one as mighty as Herakles) usurps their right to sanction, it incurs sanction of their own.

Turning to history, here is Herodotus talking about the Cretans:

οὗτοι μὲν οὕτω διεκρούσαντο τοὺς Ἕλληνας. Κρῆτες δέ, ἐπείτε σφέας παρελάμβανον οἱ ἐπὶ τούτοισι ταχθέντες Ἑλλήνων, ἐποίησαν τοιόνδε: πέμψαντες κοινῇ θεοπρόπους ἐς Δελφοὺς τὸν θεὸν ἐπειρώτων εἴ σφι ἄμεινον τιμωρέουσι γίνεται τῇ Ἑλλάδι. [2] ἡ δὲ Πυθίη ὑπεκρίνατο ‘ὦ νήπιοι, ἐπιμέμφεσθε ὅσα ὑμῖν ἐκ τῶν Μενελάου τιμωρημάτων Μίνως ἔπεμψε μηνίων δακρύματα, ὅτι οἳ μὲν οὐ συνεξεπρήξαντο αὐτῷ τὸν ἐν Καμικῷ θάνατον γενόμενον, ὑμεῖς δὲ ἐκείνοισι τὴν ἐκ Σπάρτης ἁρπασθεῖσαν ὑπ᾽ ἀνδρὸς βαρβάρου γυναῖκα.’ ταῦτα οἱ Κρῆτες ὡς ἀπενειχθέντα ἤκουσαν, ἔσχοντο τῆς τιμωρίης.

But the Cretans, when the Greeks appointed to deal with them were trying to gain their aid, acted as I will show. They sent messengers to Delphi, inquiring if it would be to their advantage to help the Greeks. [2] The Pythia answered them, “Foolish men, was not the grief enough which Minos sent upon your people for the help given to Menelaus, out of anger that those others would not help to avenge his death at Camicus, while you helped them to avenge the stealing of that woman from Sparta by a barbarian?” When this was brought to the ears of the Cretans, they would have nothing to do with aiding the Greeks.

Histories 7.169 adapted from Godley[8]

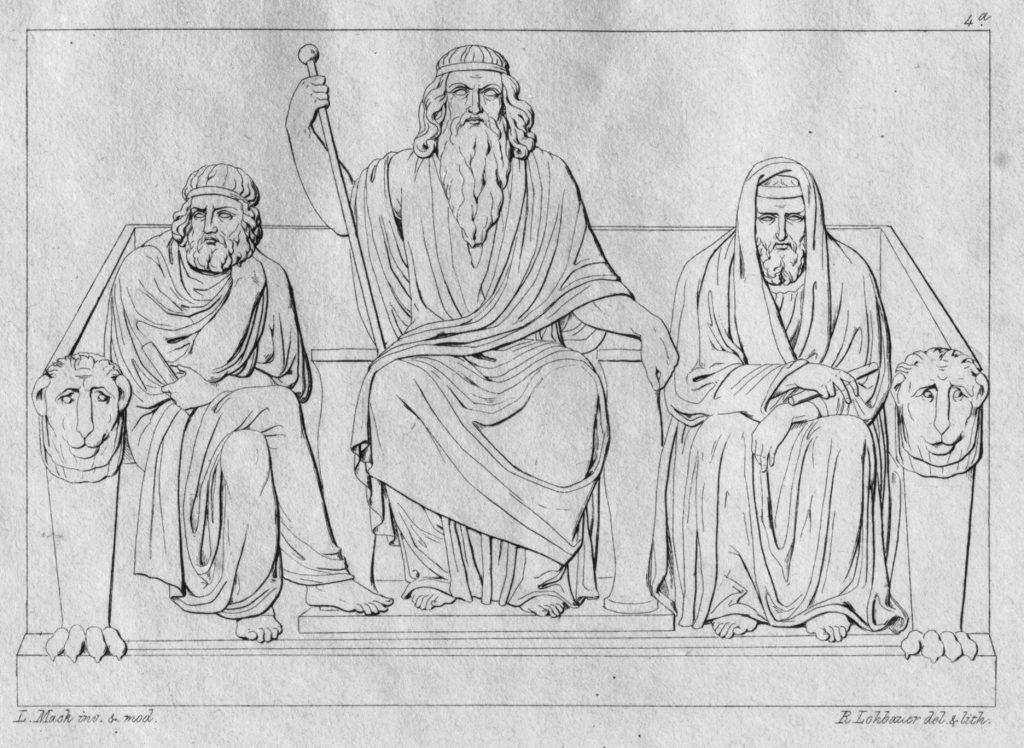

The pronouncements of the Pythia refer to aspects of the same tradition as the Iliad so the word seems to be used in a similar manner: here it is the anger of Minos which seems to have emanated after his own death. But is this mēnis in his own role of a hero, or, since it is after death, a cult hero or even a god? After all, he is listed as one of the judges in Hades, for example in Plato’s Apology of Socrates.[9]

A further passage from Herodotus takes us to the classical period:

‘ἔπεμψαν ἡμέας Ἀθηναῖοι λέγοντες ὅτι ἡμῖν βασιλεὺς ὁ Μήδων τοῦτο μὲν τὴν χώρην ἀποδιδοῖ, τοῦτο δὲ συμμάχους ἐθέλει ἐπ᾽ ἴσῃ τε καὶ ὁμοίῃ ποιήσασθαι ἄνευ τε δόλου καὶ ἀπάτης, ἐθέλει δὲ καὶ ἄλλην χώρην πρὸς τῇ ἡμετέρῃ διδόναι, τὴν ἂν αὐτοὶ ἑλώμεθα. [2] ἡμεῖς δὲ Δία τε Ἑλλήνιον αἰδεσθέντες καὶ τὴν Ἑλλάδα δεινὸν ποιεύμενοι προδοῦναι οὐ καταινέσαμεν ἀλλ᾽ ἀπειπάμεθα, καίπερ ἀδικεόμενοι ὑπ᾽ Ἑλλήνων καὶ καταπροδιδόμενοι, ἐπιστάμενοί τε ὅτι κερδαλεώτερον ἐστὶ ὁμολογέειν τῷ Πέρσῃ μᾶλλον ἤ περ πολεμέειν: οὐ μὲν οὐδὲ ὁμολογήσομεν ἑκόντες εἶναι. καὶ τὸ μὲν ἀπ᾽ ἡμέων οὕτω ἀκίβδηλον νέμεται ἐπὶ τοὺς Ἕλληνας:’

ὑμεῖς δὲ ἐς πᾶσαν ἀρρωδίην τότε ἀπικόμενοι μὴ ὁμολογήσωμεν τῷ Πέρσῃ, ἐπείτε ἐξεμάθετε τὸ ἡμέτερον φρόνημα σαφέως, ὅτι οὐδαμὰ προδώσομεν τὴν Ἑλλάδα, καὶ διότι τεῖχος ὑμῖν διὰ τοῦ Ἰσθμοῦ ἐλαυνόμενον ἐν τέλεϊ ἐστί, καὶ δὴ λόγον οὐδένα τῶν Ἀθηναίων ποιέεσθε, συνθέμενοί τε ἡμῖν τὸν Πέρσην ἀντιώσεσθαι ἐς τὴν Βοιωτίην προδεδώκατε, περιείδετέ τε προεσβαλόντα ἐς τὴν Ἀττικὴν τὸν βάρβαρον. [2] ἐς μέν νυν τὸ παρεὸν Ἀθηναῖοι ὑμῖν μηνίουσι: οὐ γὰρ ἐποιήσατε ἐπιτηδέως. νῦν δὲ ὅτι τάχος στρατιὴν ἅμα ἡμῖν ἐκέλευσαν ὑμέας ἐκπέμπειν, ὡς ἂν τὸν βάρβαρον δεκώμεθα ἐν τῇ Ἀττικῇ: ἐπειδὴ γὰρ ἡμάρτομεν τῆς Βοιωτίης, τῆς γε ἡμετέρης ἐπιτηδεότατον ἐστὶ μαχέσασθαι τὸ Θριάσιον πεδίον.’7A. “The Athenians have sent us with this message: the king of the Medes is ready to give us back our country, and to make us his confederates, equal in right and standing, in all honor and honesty, and to give us whatever land we ourselves may choose besides our own. [2] But we, since we do not want to sin against Zeus the god of Hellas and think it shameful to betray Hellas, have not consented. This we have done despite the fact that the Greeks are dealing with us wrongfully and betraying us to our hurt; furthermore, we know that it is more to our advantage to make terms with the Persians than to wage war with him, yet we will not make terms with him of our own free will. For our part, we act honestly by the Greeks;

7B. but what of you, who once were in great dread lest we should make terms with the Persian? Now that you have a clear idea of our sentiments and are sure that we will never betray Hellas, and now that the wall which you are building across the Isthmus is nearly finished, you take no account of the Athenians, but have deserted us despite all your promises that you would withstand the Persian in Boeotia, and have permitted the barbarian to march into Attica. [2] For the present, then, the Athenians are angry with you since you have acted in a manner unworthy of you. Now they ask you to send with us an army with all speed, so that we may await the foreigner’s onset in Attica; since we have lost Boeotia, in our own territory the most suitable place for a battle is the Thriasian plain.”Histories, 9.7B, adapted from Godley[10]

Here the word “be angry, have mēnis” is used in a context when the Athenians are considering their actions in terms of a collective which does, then, maybe have something in common with the way the verb is used in the Iliad even if it is not described directly in terms of epic heroes or gods. Is there still a social and collective way in which the term is used? And does the Athenians’ earlier reference to Zeus imply that their own anger is somehow sanctioned by the god?

A couple of brief examples from Plato. First, in a discussion about the definitions of laws and punishments:

νόμοι δέ, ὡς ἔοικεν, οἱ μὲν τῶν χρηστῶν ἀνθρώπων ἕνεκα γίγνονται, διδαχῆς χάριν τοῦ τίνα τρόπον ὁμιλοῦντες [880ε] ἀλλήλοις ἂν φιλοφρόνως οἰκοῖεν, οἱ δὲ τῶν τὴν παιδείαν διαφυγόντων, ἀτεράμονι χρωμένων τινὶ φύσει καὶ μηδὲν τεγχθέντων ὥστε μὴ ἐπὶ πᾶσαν ἰέναι κάκην. οὗτοι τοὺς μέλλοντας λόγους ῥηθήσεσθαι πεποιηκότες ἂν εἶεν: οἷς δὴ τοὺς νόμους ἐξ ἀνάγκης ὁ νομοθέτης ἂν νομοθετοῖ, βουλόμενος αὐτῶν μηδέποτε χρείαν γίγνεσθαι. πατρὸς γὰρ ἢ μητρὸς ἢ τούτων ἔτι προγόνων ὅστις τολμήσει ἅψασθαί ποτε βιαζόμενος αἰκίᾳ τινί, μήτε τῶν ἄνω δείσας θεῶν μῆνιν μήτε [881α] τῶν ὑπὸ γῆς τιμωριῶν λεγομένων, ἀλλὰ ὡς εἰδὼς ἃ μηδαμῶς οἶδεν, καταφρονῶν τῶν παλαιῶν καὶ ὑπὸ πάντων εἰρημένων, παρανομεῖ, τούτῳ δεῖ τινος ἀποτροπῆς ἐσχάτης. θάνατος μὲν οὖν οὐκ ἔστιν ἔσχατον, οἱ δὲ ἐν Ἅιδου τούτοισι λεγόμενοι πόνοι ἔτι τε τούτων εἰσὶ μᾶλλον ἐν ἐσχάτοις, καὶ ἀληθέστατα λέγοντες οὐδὲν ἀνύτουσιν ταῖς τοιαύταις ψυχαῖς ἀποτροπῆς

Laws, it would seem, are made partly [880e] for the sake of good men, to afford them instruction as to what manner of intercourse will best secure for them friendly association one with another, and partly also for the sake of those who have shunned education, and who, being of a stubborn nature, have had no softening treatment to prevent their taking to all manner of wickedness. It is because of these men that the laws which follow have to be stated,—laws which the lawgiver must enact of necessity, on their account, although wishing that the need for them may never arise. Whosoever shall dare to lay hands on father or mother, or their progenitors, and to use outrageous violence, fearing neither the wrath of the gods above nor that of the Avengers (as they are called) of the underworld, but scorning the ancient and worldwide traditions [881a] (thinking he knows what he knows not at all), and shall thus transgress the law,—for such a man there is needed some most severe deterrent. Death is not a most severe penalty; and the punishments we are told of in Hades for such offences, although more severe than death and described most truly, yet fail to prove any deterrent to souls such as these

Plato Laws 9.880d–880e, translation by R.G. Bury[11]

Ἱππίας

ἔστι μὲν ταῦτα, ὦ Σώκρατες, οὕτως ὡς σὺ λέγεις: εἴωθα μέντοι ἔγωγε τοὺς παλαιούς τε καὶ προτέρους ἡμῶν προτέρους τε καὶ μᾶλλον ἐγκωμιάζειν ἢ τοὺς νῦν, εὐλαβούμενος μὲν φθόνον τῶν ζώντων, φοβούμενος δὲ μῆνιν τῶν τετελευτηκότων.Hippias

That, Socrates, is exactly as you say. I, however, am in the habit of praising the ancients and our predecessors rather than the men of the present day, and more greatly, as a precaution against the envy of the living and through fear of the wrath of those who are dead.Plato Greater Hippias 282a Translated by W.R.M. Lamb[12]

Please join me in the forum to continue the discussion and to share other passages and examples.

For those without Greek, the term is tracked in the texts in the Sourcebook. For those who can read a little Greek, you can find the word in the Perseus corpus of Greek texts online, many of which have English translations alongside. But be aware that such a search might also show other unrelated words that are similar in form.

Terms related to mēnis

These are a selection of related terms also mentioned in Muellner’s book, so are included here for reference.

mēnis “wrath”

ópis “wrath”

mēni-thmós “wrath”

mēníō “have mênis’”

apomēníō “invoke mênis”

Notes

[1] H24H Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA: 2013. Available online at CHS.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013

[2] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2018.08.06.

Available online

[3] Muellner, Leonard. 1996. The Anger of Achilles Mênis in Greek Epic Cornell University Press. Ithaca, N.Y.; London. Available online at CHS

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_MuellnerL.The_Anger_of_Achilles.1996

[4] Muellner 1996. page 8.

[5] Edmonds, J.M. 1931. Elegy and Iambus, Volume I. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; London, Heinemann. Available online on Perseus

[6] Muellner 1996. page 35.

[7] Jebb, Sir Richard. 1892. The Trachiniae of Sophocles. Edited with introduction and notes by Sir Richard Jebb. Sir Richard Jebb. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Online at Perseus

[8] Herodotus, Histories 7.8. Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. 1920. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. Online at Perseus

[9] Plato The Apology of Socrates, 40e, Sourcebook.

[10] Herodotus, Histories 9.78. Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. 1920. Cambridge. Harvard University Press.

Online at Perseus

[11] Plato Laws

Greek: Platonis Opera, ed. John Burnet. Oxford University Press. 1903. Online at Perseus.

English: Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vols. 10 & 11 translated by R.G. Bury. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1967 & 1968. Online at Perseus

[12] Plato Greater Hippias

Greek: Platonis Opera, ed. John Burnet. Oxford University Press. 1903. Online at Perseus

English: Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 9 translated by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925. Online at Perseus

Online texts accessed September 28, 2018.

Updated March 3 2021 to add references [11] and [12]

Image credits

von Kaulbach, Wilhelm. Demeter 1830–31. Sammlung Pinakothek, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen. Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Egisto Sani (photo) Zeus and thunderbolt, Berlin Painter, Attic red-necked amphora c 480-470 BCE, Louvre. Flickr, Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Fuseli, Henry. Night and Her Children Aither and Hemera (Hesiod Theogony) c 1810–1815. Metropolitan Museum of Art, public domain.

Jastrow (photo) Eurytios [=Eurytus] and Herakles at symposium, Corinthian column-krater, c 600 BCE, Louvre. Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons CC BY 2.5

Mack, Ludwig / Lithograph Lohbauer, Rudolph, Die Unterwelt, showing Minos, Aiakos, and Rhadamanthus, as judges of the dead in Hades. 1824–1829, Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

CNG coins http://www.cngcoins.com Coin: Head of Jupiter and Thunderbolt,, Epeiros c 234–168 BCE. Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website. Images accessed September 28, 2018.

______

Sarah Scott has a degree in Language from the University of York where she specialized in philology, and has worked as an editor, technical author, and documentation manager. She is the Executive Producer for the HeroesX project, and one of the Executive Editors of the HeroesX Sourcebook. She is an active participant and member of the editorial team in Kosmos Society, with a particular interest in content development, document management, word studies, language learning, comparative linguistics, and digital humanities.