This month’s Core Vocabulary discussion, based on terms listed in The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours[1] and tracked in the Sourcebook[2] is “biā [βία] (biē [βίη] in the language of Homeric poetry) ‘force, violence’.” As we read passages together, among the questions we might ask are: what kinds of force are exhibited, and is it ever depicted as a desirable or undesirable quality?

Here are a few examples to start the discussion.

The Theogony depicts it originally, as with so many other qualities, in the form of a goddess, or perhaps a personification:

And Styx, daughter of Okeanos, after union with Pallas, bore within the house Zelos and beauteous-ankled Victory; 385 and she gave birth to Strength [Kratos] and Force [Biē], illustrious children, whose abode is not apart from Zeus, nor is there any seat, or any way, where the god does not go before them; but always they sit beside deep-thundering Zeus.

Hesiod Theogony 383–388, Sourcebook

According to Hesiod, such force or violence is typical of the Bronze Generation:

[145]…Their minds were set on the woeful deeds of Arēs

146 and on acts of hubris. Grain

147 they did not eat, but their hard-dispositioned heart [thūmos] was made of hard rock.

148 They were forbidding: they had great force [biē] and overpowering hands

149 growing out of their shoulders, with firm foundations for limbs.

150 Their implements were bronze, their houses were bronze,

151 and they did their work with bronze. There was no black iron.

152 And they were wiped out when they killed each other with their own hands,

153 and went nameless to the dank house of chill Hādēs

Hesiod Works & Days 145–153

Apollo speaks to the gods about Achilles’ outrageous treatment of Hector’s body, and, as in the Works & Days passage such strength can be out of control if it is not tempered with right-thinking:

[40] His thinking [phrenes] is not right and his sense of noos 41 is not flexible within his breast, but like a lion he knows savage ways. 42 —a lion that yields to its strength [biē] and overweening thūmos, 43 and goes after the sheep of men, in order to get a feast [dais]. Even so has Achilles flung aside all pity, [45] and all that decency [aidōs] which at once so greatly hurts yet greatly benefits anyone who abides by it.

Iliad 24.40–45, Sourcebook

We see here the lion is a creature that is not able to control itself: biē is part of their nature. This perhaps also applies to the passage when Odysseus’ men are taken by force, as in the horrific description of Scylla:

We could see the bottom of the whirlpool all black with sand and mud, and the men were at their wit’s ends for fear. While we were taken up with this, and were expecting each moment to be our last, [245] Scylla pounced down suddenly upon us and with violence [biē] snatched up my six best men. I was looking at once after both ship and men, and in a moment I saw their hands and feet ever so high above me, struggling in the air as Scylla was carrying them off, and I heard them call out my name [250] in one last despairing cry. As a fisherman, seated, spear in hand, upon some jutting rock throws bait into the water to deceive the poor little fishes, and spears them with the ox’s horn with which his spear is shod, throwing them gasping on to the land as he catches them one by one— [255] even so did Scylla land these panting creatures on her rock and munch them up at the mouth of her den, while they screamed and stretched out their hands to me in their mortal agony.

Odyssey 12.242–257, Sourcebook

The word also seems to be used in contexts where people or wealth are taken by force, for example as Croesus mentions when he gives advice to Cyrus:

The Persians have hubris by nature and lack wealth. So if you allow them to pillage and gain great wealth, this is what you may expect from them: expect that whoever of them acquires the most will rise in rebellion against you. Now if what I say pleases you, do this: place guards from your bodyguard at all the gates, who will take the goods from those who are carrying them out, by saying that it is necessary for them to give a tithe to Zeus. You will not be hated by them for taking their things by force [biā], and they will admit that you are acting justly [= doing what is dikaion] and willingly surrender it.

Herodotus 1.89, Sourcebook

On the plus side, it seems to be a quality that is needed to be effective in battle. Nestor looks back on the days when he had enough strength and force to face an enemy in single combat:

Son of Atreus, I too would gladly be the man I was when I slew mighty Ereuthalion; [320] but the gods will not give us everything at one and the same time. I was then young, and now I am old; still I can go with my horsemen and give them that counsel which old men have a right to give. The wielding of the spear I leave to those [325] who are younger and have more force [biē] than myself.

Iliad 4.317–325, Sourcebook

He goes on to tell the story in Rhapsody 7, and again regrets the passing of his former strength, again as a way of trying to shame younger men into stepping forward.

[150] So, wearing his armor [of Arēithoös], he [Ereuthalion] was challenging all the best to fight him. 151 But they were all afraid and trembling: no one undertook to do it. 152 I was the only one, driven to fight by my heart [thūmos] which was ready to undertake much, 153 with all its boldness, even though I was the youngest of them all. 154 I fought him, and Athena gave me fame. [155] For I killed the biggest and the best man: 156 he sprawled in his great bulk from here to here. 157 If only I were that young! If only my biē had remained as it was! For the son of Priam would then soon find one who would face him. But you, foremost among the whole army of warriors though you be, [160] have none of you any stomach for fighting Hector.

Iliad 7.150–160, Sourcebook

The strength of Telemachus is also described as biē, and on his father’s signal he is able to curb this strength in order to allow their plans to come to fruition:

…he went on to the pavement to make trial of the bow; [125] three times did he tug at it, trying with all his might to draw the string, and three times he had to rest his strength [biē], though he had hoped to string the bow and shoot through the iron. He was trying, with all his strength [biē], for the fourth time, and would have strung it had not Odysseus made a sign to check him in spite of all his eagerness. [130] So he said:

“Alas! I shall either be always feeble and of no prowess, or I am too young, and have not yet reached my full strength so as to be able to hold my own if any one attacks me. You others, therefore, who have more strength [biē] than I, [135] make trial of the bow and get this contest [āthlos] settled.”

Odyssey 21.124–142, Sourcebook

So how are we to think of the biē of the suitors? And what about that of Odysseus who, as it turns out, is the only one who is able to string the bow?

Does biē or biā require other qualities for it to be effective without the person descending to the nature of a beast, and how can it be stopped or redirected? Are there occasions when it is admired, or harnessed effectively? Which heroes display this quality, and when?

Please join the forum discussion to share further examples of how this word is used.

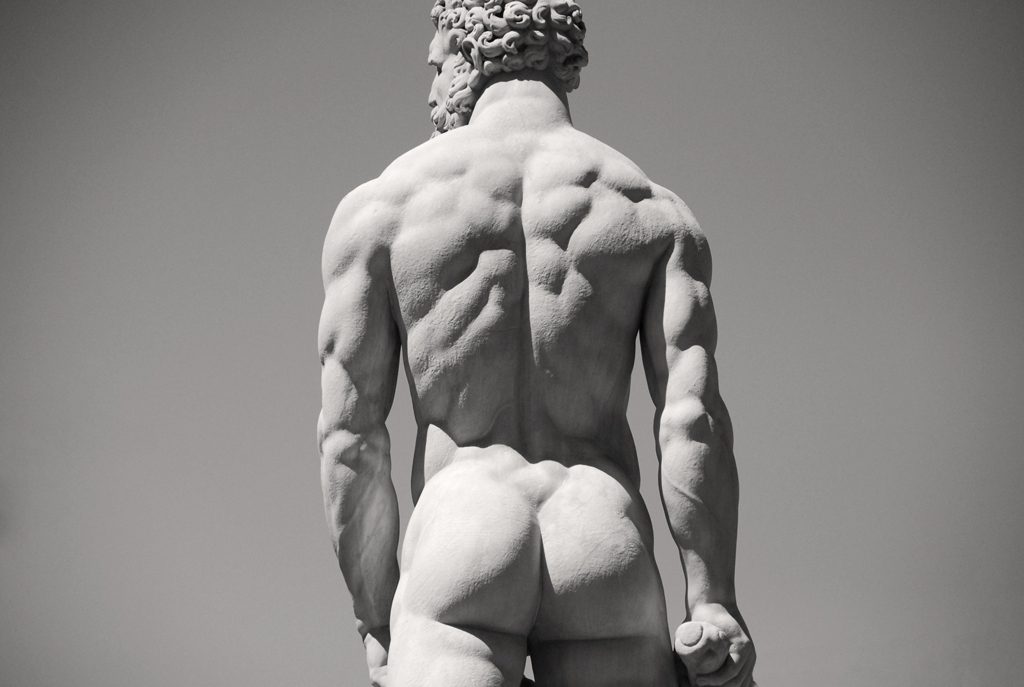

And how would you choose to depict it visually?

References

[1] Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013

[2] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor.

Image credits

Cyberuly (photo): Detail from Baccio Bandinelli Statue of Heracles and Cacus 1530–1534, Piazza della Signora, Florence. Creative Commons CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Walters Art Museum (photo): Pamphaios/Nikosthenes Painter Red-Figure Kylix with Running Warriors, circa 495 BCE. Creative Commons CC0

BabelStone (photo): Gold coin of Croesus, Lydian, circa 550BCE. British Museum. Creative Commons CC0 1.0 public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Classical Numismatic Group Inc (photo): Sextus Pompeius 42-40 BCE AR Denarius, depicting galley adorned with aquila, sceptre and trident before the Colonna Rhegina, decorated with a statue of Neptune/Poseidon—the monster Scylla, her torso of dogs and fishes, wielding a rudder as a club. Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Bibi Saint-Pol (photo): Ixion Painter Mnêstêrophonía: slaughter of the suitors by Odysseus, Telemachus and Eumeus (right). Side A from a Campanian (Capouan?) red-figure bell-krater, c 330 BCE. Louvre. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

___

Sarah Scott has a degree in Language from the University of York, and has worked as an editor, technical author, and documentation manager. She is Associate Producer for the HeroesX project, and one of the Executive Editors of the HeroesX Sourcebook. She is an active participant and member of the editorial team in Kosmos Society, with a particular interest in content development, document management, word studies, language learning, comparative linguistics, and digital humanities.