A guest post by Sarah Scott

This month I looked for sophos [σοφός] ‘skilled, skilled in understanding special language’; sophiā [σοφία] ‘being sophos’.[1]

For if one possesses good things without a lengthy ordeal [ponos], many think that he is sophos, that he is not one of the ignorant, [75] the way he arranges his life, they think, with straight-planned stratagems. But that is not ordained to be, in this world of men. It is the superhuman force [daimōn] who provides, exalting different men at different times, at other times bringing them down in due proportion.

(Pindar Pythian 8, Sourcebook[1])

εἰ γάρ τις ἐσλὰ πέπαται μὴ σὺν μακρῷ πόνῳ,

πολλοῖς σοφὸς δοκεῖ πεδ᾽ ἀφρόνων

βίον κορυσσέμεν ὀρθοβούλοισι μαχαναῖς: 75

τὰ δ᾽ οὐκ ἐπ᾽ ἀνδράσι κεῖται: δαίμων δὲ παρίσχει,

[110] ἄλλοτ᾽ ἄλλον ὕπερθε βάλλων,[3]

Here being sophos is contrasted with ignorance. However, it seems that if someone ‘possesses good things’ being sophos is not enough: a daimōn is responsible.

Orestes

Orestes

Schooled in misery, I know many purification rituals, and I know when it is dikē to speak and similarly when to be silent; and in this case, I have been ordered to speak by a sophos teacher. 280 For the blood slumbers and fades from my hand—the pollution [miasma] of matricide is washed away; while the blood was still fresh, it was driven away at the hearth of the god Phoebus by expiatory sacrifices of swine.

(Aeschylus Eumenides 276–283, Sourcebook)

ἐγὼ διδαχθεὶς ἐν κακοῖς ἐπίσταμαι

πολλοὺς καθαρμούς, καὶ λέγειν ὅπου δίκη

σιγᾶν θ᾽ ὁμοίως: ἐν δὲ τῷδε πράγματι

φωνεῖν ἐτάχθην πρὸς σοφοῦ διδασκάλου.

βρίζει γὰρ αἷμα καὶ μαραίνεται χερός, 280

μητροκτόνον μίασμα δ᾽ ἔκπλυτον πέλει:

ποταίνιον γὰρ ὂν πρὸς ἑστίᾳ θεοῦ

Φοίβου καθαρμοῖς ἠλάθη χοιροκτόνοις.

What I noticed here is a specific god, Phoebus in the Aeschylus, is behind what happens, and Orestes is being directed to speak by someone who is sophos. This might relate to oracles and seers, and we also find that a seer like Teiresias might be described as sophos, for example in these two passages:

Oedipus

Did this mantis possess this skill in those days?

Creon

He was sophos as now, and held in equal tīmē.

(Sophocles Oedipus Tyrannus 562–3, Sourcebook)

Οἰδίπους

τότ᾽ οὖν ὁ μάντις οὗτος ἦν ἐν τῇ τέχνῃ;

Κρέων

σοφός γ᾽ ὁμοίως κἀξ ἴσου τιμώμενος.

Kadmos

Most philos, from inside the house I heard and recognized your wise [sophē] voice—the voice of a sophos man— 180 and have come with this equipment of the god. To the best of our abilities we must extol him, the child of my daughter. Where is it necessary to take the khoros, where must we put our feet and 185 shake our grey heads? Lead me, an old man, Teiresias, yourself old. For you are sophos. And so I would not tire night or day striking the ground with the thyrsos. Gladly I have forgotten that we are old.

(Euripides Bacchae 179–188, Sourcebook)

ὦ φίλταθ᾽, ὡς σὴν γῆρυν ᾐσθόμην κλύων

σοφὴν σοφοῦ παρ᾽ ἀνδρός, ἐν δόμοισιν ὤν:

ἥκω δ᾽ ἕτοιμος τήνδ᾽ ἔχων σκευὴν θεοῦ: 180

δεῖ γάρ νιν ὄντα παῖδα θυγατρὸς ἐξ ἐμῆς

Διόνυσον ὃς πέφηνεν ἀνθρώποις θεὸς

ὅσον καθ᾽ ἡμᾶς δυνατὸν αὔξεσθαι μέγαν.

ποῖ δεῖ χορεύειν, ποῖ καθιστάναι πόδα

καὶ κρᾶτα σεῖσαι πολιόν; ἐξηγοῦ σύ μοι 185

γέρων γέροντι, Τειρεσία: σὺ γὰρ σοφός.

ὡς οὐ κάμοιμ᾽ ἂν οὔτε νύκτ᾽ οὔθ᾽ ἡμέραν

θύρσῳ κροτῶν γῆν: ἐπιλελήσμεθ᾽ ἡδέως

γέροντες ὄντες.

I wonder if the word relates therefore not only to understanding but also delivering special language.

Hippolytus

Father, your menos and the intensity of your phrenes are terrible. Although your arguments are well put, if one lays them bare, your charge is no good. I have little skill in speaking before a crowd; I am more sophos with my own contemporaries and small groups. But this is fate: those whom the sophoi dislike are more skilled in addressing a crowd. 990 Yet it is necessary in the present circumstance to break my silence.

(Euripides Hippolytus 983–991)

πάτερ, μένος μὲν ξύντασίς τε σῶν φρενῶν

δεινή: τὸ μέντοι πρᾶγμ᾽, ἔχον καλοὺς λόγους,

εἴ τις διαπτύξειεν οὐ καλὸν τόδε. 985

ἐγὼ δ᾽ ἄκομψος εἰς ὄχλον δοῦναι λόγον,

ἐς ἥλικας δὲ κὠλίγους σοφώτερος:

ἔχει δὲ μοῖραν καὶ τόδ᾽: οἱ γὰρ ἐν σοφοῖς

φαῦλοι παρ᾽ ὄχλῳ μουσικώτεροι λέγειν.

ὅμως δ᾽ ἀνάγκη, ξυμφορᾶς ἀφιγμένης, 990

γλῶσσάν μ᾽ ἀφεῖναι.

And again we see the importance of knowing when to speak and when to be silent, as with the Eumenides passage above.

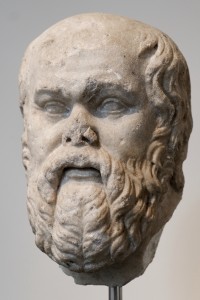

My final passage is from Plato’s Socrates:

Men of Athens, this reputation of mine has come of a certain sort of wisdom [sophiā] which I possess. If you ask me what kind of wisdom [sophiā], I reply, such wisdom [sophiā] as is attainable by man, for to that extent I am inclined to believe that I am wise [sophos]; [20e] whereas the persons of whom I was speaking have a superhuman wisdom [sophiā], which I may fail to describe, because I have it not myself; and he who says that I have, speaks falsely, and is taking away my character. And here, O men of Athens, I must beg you not to interrupt me, even if I seem to say something extravagant. For the word which I will speak is not mine. I will refer you to a witness who is worthy of credit, and will tell you about my wisdom [sophiā]—whether I have any, and of what sort—and that witness shall be the god of Delphi.

Men of Athens, this reputation of mine has come of a certain sort of wisdom [sophiā] which I possess. If you ask me what kind of wisdom [sophiā], I reply, such wisdom [sophiā] as is attainable by man, for to that extent I am inclined to believe that I am wise [sophos]; [20e] whereas the persons of whom I was speaking have a superhuman wisdom [sophiā], which I may fail to describe, because I have it not myself; and he who says that I have, speaks falsely, and is taking away my character. And here, O men of Athens, I must beg you not to interrupt me, even if I seem to say something extravagant. For the word which I will speak is not mine. I will refer you to a witness who is worthy of credit, and will tell you about my wisdom [sophiā]—whether I have any, and of what sort—and that witness shall be the god of Delphi.

(Plato Apology of Socrates 20d–20e, Sourcebook)

ἐγὼ γάρ, ὦ ἄνδρες Ἀθηναῖοι, δι᾽ οὐδὲν ἀλλ᾽ ἢ διὰ σοφίαν τινὰ τοῦτο τὸ ὄνομα ἔσχηκα. ποίαν δὴ σοφίαν ταύτην; ἥπερ ἐστὶν ἴσως ἀνθρωπίνη σοφία: τῷ ὄντι γὰρ κινδυνεύω ταύτην εἶναι σοφός. οὗτοι δὲ τάχ᾽ ἄν, οὓς ἄρτι [20ε] ἔλεγον, μείζω τινὰ ἢ κατ᾽ ἄνθρωπον σοφίαν σοφοὶ εἶεν, ἢ οὐκ ἔχω τί λέγω: οὐ γὰρ δὴ ἔγωγε αὐτὴν ἐπίσταμαι, ἀλλ᾽ ὅστις φησὶ ψεύδεταί τε καὶ ἐπὶ διαβολῇ τῇ ἐμῇ λέγει. καί μοι, ὦ ἄνδρες Ἀθηναῖοι, μὴ θορυβήσητε, μηδ᾽ ἐὰν δόξω τι ὑμῖν μέγα λέγειν: οὐ γὰρ ἐμὸν ἐρῶ τὸν λόγον ὃν ἂν λέγω, ἀλλ᾽ εἰς ἀξιόχρεων ὑμῖν τὸν λέγοντα ἀνοίσω. τῆς γὰρ ἐμῆς, εἰ δή τίς ἐστιν σοφία καὶ οἵα, μάρτυρα ὑμῖν παρέξομαι τὸν θεὸν τὸν ἐν Δελφοῖς.

Although the word is translated here as ‘wise’ (or ‘wisdom’) I notice that the passage again relates to speaking, and again invokes Apollo.

There are many other places in the Sourcebook—and in other ancient Greek texts—where these words appear. I would be interested to see what others might find about the context in which the word appears, and whether you notice any different relationships or situations, so I hope you will join me in discussion.

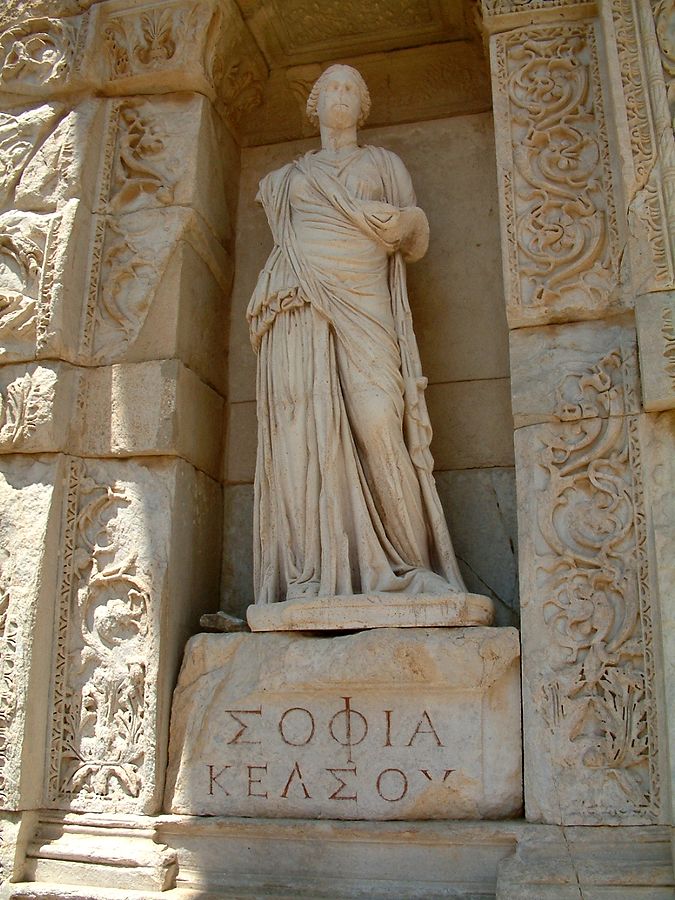

I have made my selection of images from pictures that are freely available with open source, public domain, or Creative Commons licenses. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. What sorts of images would you choose to visualize these Core Vocab words?

References

[1] Definition from Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013

[2] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor.

[3] All Greek texts from Perseus perseus.tufts.edu

Updated March 2021 to add References

Image credits

Radomil: Sophia, in the Celsus Library in Ephesus, Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0

Jastrow (photo): Python (as painter) Orestes at Delphi: Paestan red-figured bell-krater c 300BCE (British Museum), public domain

Marie-Lan Nguyen: Head of Socrates. Roman copy of the Imperial era (AD 1st–2nd century) after a Greek original of ca. 350 BC often attributed to Lysippos. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Creative Commons CC BY 2.5

___

Sarah Scott has a degree in Language from the University of York where she specialized in philology, and has worked as an editor, technical author, and documentation manager. She is the Associate Producer for the HeroesX project, and one of the Executive Editors of the HeroesX Sourcebook. She is an active participant and member of the editorial team in Hour 25, with a particular interest in content development, document management, word studies, language learning, comparative linguistics, and digital humanities.