~ A guest blog by Sarah Scott & Janet Ozsolak and the Oinops Study Group ~

Zeus struck my ship with his thunderbolts,

and broke it up in the middle of the wine-faced [oinops] sea [pontos]

(Odyssey vii, 249–252)

Although we had searched on the Greek word oinops, once we had the list of passages we had been reading them in translation. The word ‘sea’ had been prominent in the group’s findings as a term that was described by oinops¸ and we wanted to know more about the Greek word(s) for ‘sea’.

There are three main words in Homeric poetry in reference to sea: θάλασσα [thalassa], ἅλς [hals] and πόντος [pontos].

What About Meter?

How did the song culture tradition choose which one to use? I told Sarah that my immediate response was fitting into meter. Homeric poetry was sung in hexameter. For the purposes of this discussion, each line is divided into six feet, and each foot contains either two longs or one + long two short syllables:

The form of this medium of epic poetry, which calls itself kleos or klea andrōn, is called the dactylic hexameter. Over 15,000 of these dactylic hexameter lines make up the Iliad. Here is the basic rhythm of this form:

— u u — u u — u u — u u — u u — —

(“— ” = long syllable, “u” = short syllable)

(Gregory Nagy, The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours, 2§27)

Could meter have played a role in choosing which sea word was to be sung?

The word pontos has two syllables, hals has one, and thalassa has three, so that might seem to be a reason why one word is used over another.

Why Different Words for Sea?

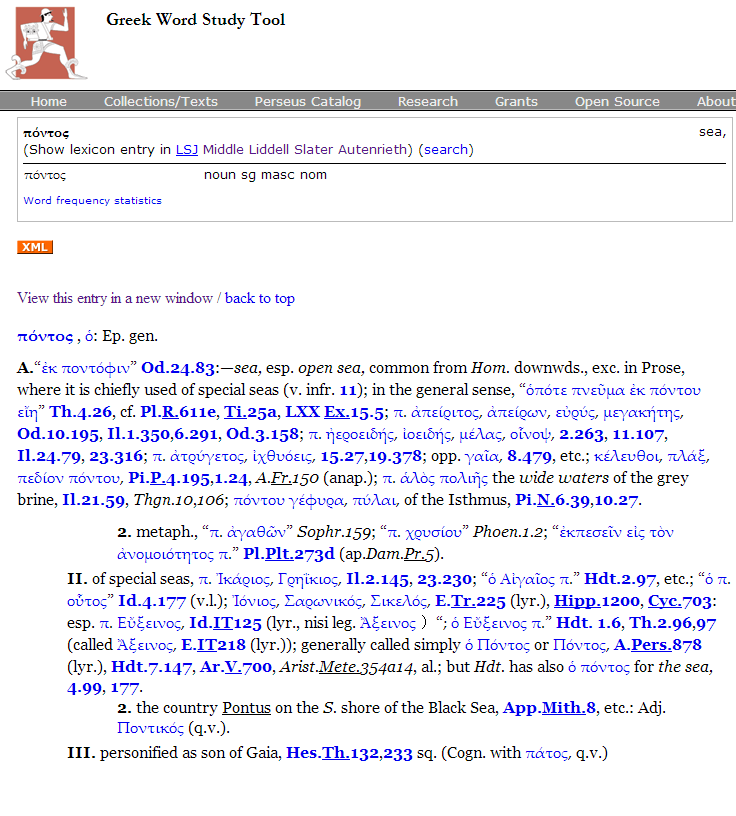

But we also noticed that there are also some differences in the definitions of the different words for sea. On Perseus we looked at the dictionary entries in Middle Liddell (which focuses on Homeric words):

- hals is described as ‘sea (generally of shallow water near shore)’ and it is related to a word meaning ‘salt’,

- thalassa is explained as ‘the sea, Hom., etc.; when he uses it of a particular sea, he means the Mediterranean”

- pontos is defined as ‘the sea, esp. the open sea.’

There are also more extended dictionary entries in LSJ on Perseus which includes citations from a variety of authors.

We found Joel Christensen’s video Decoding Ancient Greek Dictionary Definitions helpful in understanding how the LSJ entries are laid out.

Phrases in Oral Poetry

In Homeric poetry, each sea word can be accompanied with an adjective, for example a roaring sea, gray sea, deep sea or wine-faced sea.

When the group looked at the word oinops in the Greek passages, it clearly established that the word describes pontos and not thalassa or hals. For our investigation into the theme of the sea, we looked into thalassa and hals briefly since they were never used with the epithet oinops. Only pontos accompanied oinops.

We have not exhausted the investigation into meter with respect to different words for sea, but since in this group we were focusing on oinops, we left ourselves a ‘placeholder’ for a possible new word study.

After going through two sessions of the HeroesX project and learning about the song culture tradition and importance of the language used, we suspected that “meter” alone cannot explain why. A passage from Casey Dué and Mary Ebbott’s Iliad X and the Poetics of Ambush supported our view, citing John Miles Foley’s works:

“As in language generally, Foley argues following Lord, that the poet’s thought, not meter, is the driving force of expression. One way in which oral poetry is “more so,” Foley has shown, is that the compositional units that singers think and compose in are not individual words, but phrases, lines, and even combinations of multiple lines that have a meaning greater than the sum of the individual words. Both the singer and the audience who are within the tradition have easy access to this greater meaning because of their familiarity with the conventions of this language.” Foley, who has continued the comparative work with the South Slavic oral tradition that Parry and Lord began (see e.g. Foley 1999:37–111), has built on this idea to arrive at his general dictum that “oral poetry works like language, only more so” (Foley 2002:127–128). (Our emphasis)

(Iliad X and the Poetics of Ambush, Essay 1)

Homeric verse in particular also manifests economy in its use of formulaic phrases and expressions. Albert Lord refers to Milman Parry’s analysis of this feature or oral composition-in-performance:

Once a singer has solved a particular problem in versemaking, does he attempt to find any other solution for it? In other words, does he has two formulas, metrically equivalent, which express the same essential idea? Parry has shown how “thrifty” Homer was in this respect.

(Albert B. Lord The Singer of Tales, second edition, p50)

Looking at Phrases in more Detail

There were three different prepositions in the passages that included oinops:

- ἐν(ὶ) [en] (in, on)

- ἐπὶ [epi] (cross, on, motion towards)

- εἰς [eis] (to, into)

We wondered whether there was any difference between the passages that referred to ‘across the wine-faced sea’ and those that referred to being ‘on the wine-faced sea’ or ‘to the wine-faced sea?

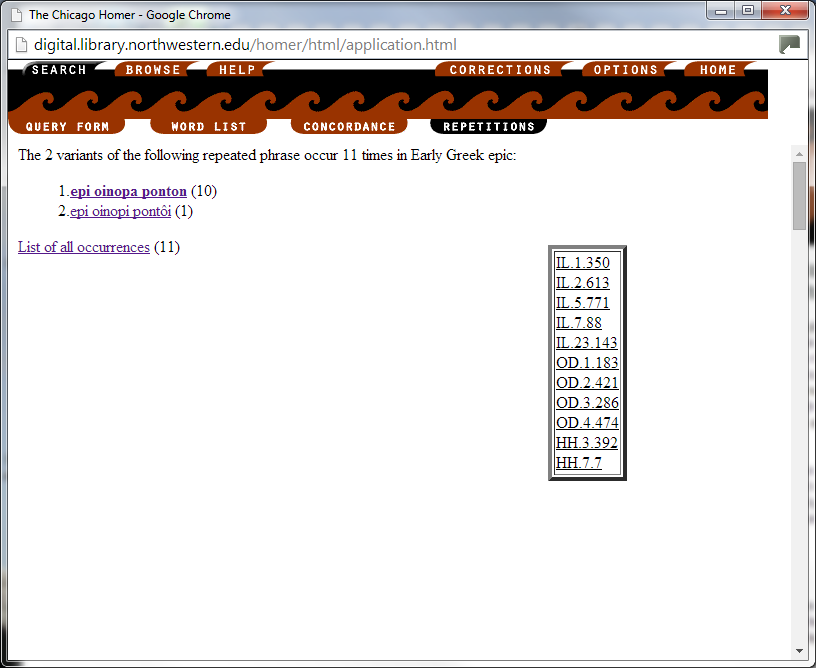

How did we do this? We used the Chicago Homer website, which provides an easy, visual way to search for a given phrase.

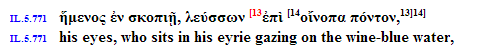

In this example, we located the phrase in one of our passages:

By clicking on the number that delimits the phrase (the number 13 in this case), we were given a list of all the other passages where this exact phrase occurs:

Results screen in the Chicago Homer

Results screen in the Chicago Homer

We were then able to click through and look at each passage that included the phrase. These are the passages listed by preposition, and what we noticed as common themes in these passages when we looked at them closely in these groupings:

In, on: ἐνὶ [eni]

Iliad XXIII, 316; Odyssey v, 132, Odyssey v, 221; Odyssey vii, 250; Odyssey xii, 388; Odyssey xix, 172; Odyssey xix, 274; Works and Days, 622

All but one of these are associated with extreme danger, being zapped, being lost, and being right out at sea, not getting back, such as:

Zeus struck my ship with his thunderbolts,

and broke it up in the middle of the wine-faced [oinops] sea [pontos].

(Odyssey vii, 249–252, modified from Sourcebook[1])

The one exception is the description of Crete in Odyssey xix, 172. Now Odysseus is lying as he so often does about being from Crete. But it really stands out as being completely an opposite sense. Looking at Crete and why Odysseus claims to be from there could be another whole research topic! But here, does it stand in for being lost at sea (lost identity)?

Across, on, motion towards: ἐπὶ [epi]

Iliad I, 350; Iliad II, 613; Iliad V, 771; Iliad VII, 88; Iliad XXIII, 143; Odyssey i, 183; Odyssey ii, 421; Odyssey iii, 286; Odyssey iv, 474; Homeric Hymn to Apollo, 392; Homeric Hymn to Dionysus, 7.

Most of the occurrences of oinops in Iliad were with epi, such as Achilles looking gloomily out to sea pining for a homecoming that will never happen, or the imaginary sailor looking at the burial place:

I will give up his body,

that the Achaeans may bury him at their ships, and then build him a tomb [sēma] by the wide waters of the Hellespont. Then will one say hereafter as he sails his ship over the wine-faced [oinops] sea [pontos], ‘This is the marker [sēma] of one who died long since

a champion who was slain by mighty Hector.’ Thus will one say, and my fame [kleos] shall not perish.”

(Iliad VII, 84–92, modified from our Sourcebook)

The exception for this phrase is the Arkadians in the Catalogue of Ships (Iliad II, 613): Agamemnon had to provide them with ships since they know nothing of the sea. And this would be the possible resting place of Odysseus’ oar/winnowing shovel.

The occurrences in Odyssey were all in the first four scrolls, the Telemakhiad. The first two of these are in relation to Athena and Telemakhus himself; the other two are in the accounts by Nestor and Menelaos.

In the Homeric Hymns than the god is present in both cases, for example:

|1 About Dionysus son of most glorious Semele |2 my mind will connect, how it was that he made an appearance [phainesthai] by the shore of the barren sea |3 on a prominent headland, looking like a young man |4 at the beginning of adolescence. Beautiful were the locks of hair as they waved in the breeze surrounding him. |5They were the color of deep blue. And a cloak he wore over his strong shoulders, |6 color of purple. Then, all of a sudden, men seen from a ship with fine benches |7 – men who were pirates – came into view, as they were sailing over the wine-faced [oinops] sea [pontos].

(Homeric Hymn to Dionysus, 1–7, modified from our Sourcebook)

In all the passages with epi, the sense of looking is often present (as explored last time in ‘Seeing Oinops through a Different Lens‘), and over or across.

To, into: εἰς [eis]

Odyssey v, 349; Works and Days, 817

Both passages with εἰς were from the perspective from land and sending something out into the sea: Ino’s veil and a ship, respectively.

Looking for Connections

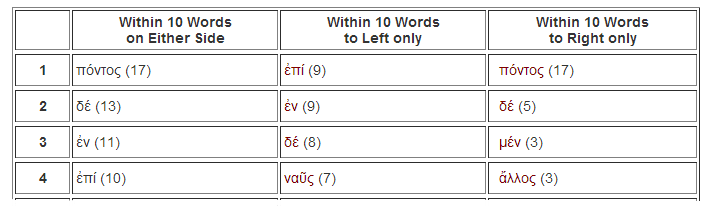

We then did a different search, using PhiloLogic on Perseus, to look for collocates (using the ‘Refined Search Results’ options), to see if there were any other words that frequently occurred in proximity to oinops that we might not have noticed during our close readings.

The results showed that, as we expected, the most frequent word was pontos; other frequent words were prepositions. The word ναῦς [naus, ‘boat’] occurs seven times within 10 words of oinops, so we thought these passages might be worth looking at in more detail.

By clicking on the word, we found the list of passages in which naus appeared, and made a note of them. All seven instances were in the passages we had been looking at, but it suggested that these particular passages might have something in common. (The passages in question were: Iliad II, 610, Iliad VII 85, Odyssey i, 180, Odyssey v, 130; Odyssey vii, 250, Odyssey xii, 385, Odyssey xix, 270).

Further down the list were some other words, that also occurred in our passages, and which again we had been noticing in our close readings. We also ran the search to see which words appeared within 3 words of oinops, and these are the top results:

Within 3 words:

- πλέω [pleō, ‘to sail’]: Iliad VII, 85; Odyssey i, 180; Odyssey iv, 470

- κεάζω [keazō, ‘to split, cleave; to shatter; sever, separate, divide forcibly’]: Odyssey v, 130; Odyssey vii, 250; Odyssey xii, 385

- ἄλλος [allos, ‘other, another’]: Iliad XXIII, 140; Odyssey v, 130; Odyssey vii, 250

Within 10 words:

- Θοός [thoos ‘1. Quick, active. 2. Sharp, pointed (of rocky islands or headlands)]’: Iliad XXIII, 315; Odyssey v, 130; Odyssey vii, 250; Odyssey xii, 385; Homeric Hymn 3, 390

- ὁράω [horaō, ‘to see, to look’]: Iliad I, 350; Iliad V, 770; Iliad V, 771; Iliad XXIII, 142

- κεραυνός [keraunos, ‘thunderbolt, thunder and lightning’]: Odyssey v, 130; Odyssey vii, 250; Odyssey xii, 385

The collocation results seem to confirm the general sense we had from close reading in context that there is a sense of danger, of headlands, and of seeing.

In the case of our oinops study we had a small number of passages that could easily be divided between us, and we had been able to find these words through our close readings and through sharing our findings in discussions.

When we looked at the results from the Chicago Homer and from PhiloLogic on Perseus, we agreed that these tools and searches might be useful if we were studying a word that occurred much more frequently than oinops because they would help us to find potentially recurring themes and make it easier to choose a selection of passages to read in more detail.

The Connection of Oinops with Pontos

Pontos, even though mentioned in Iliad 44 times, only 6 instances are with oinops, “wine-faced”; and in Odyssey the word pontos occurs 98 times, and with oinops 12. (and in Odyssey, thalassa occurs more frequently than pontos.) The word pontos may sound familiar to you, and you are right. In the HeroesX project, Professor Nagy talked about pontos in Hour 24[2]:

“The ‘Hellespont’, or Hellēspontos in Greek, is mentioned by name at line 82 of Odyssey xxiv as I quoted it in Text D. In that same passage, we saw that the tumulus of Achilles is flashing a beacon light of salvation for sailors whose lives are threatened by the dangerous waters of the sea – and the word for ‘sea’ is pontos at line 84. As I have shown in an earlier project, the link between the name Hellēs-pontos for ‘Hellespont’ at line 82 and the word pontos for ‘sea’ at line 84 is most significant in the light of the etymology of pontos, which shows the following cognates in Indo-European languages other than Greek:

Indic pánthāḥ, ‘crossing’, from one given point to another: such a ‘crossing’ is both dangerous and sacralizing.

Latin pōns (genitive pontis), ‘bridge’. Most relevant is the report of Varro (On the Latin language 5.83) about a famous bridge, the Pōns Sublicius, which spans the river Tiber in Rome: the prototype of this bridge was built and ritually maintained by a prototype of the chief priest of Rome, the pontifex maximus. The Latin word ponti-fex means, etymologically, ‘the one who makes the crossing’.

Armenian hun, ‘fording’.”

(H24H 24§20)

What Do You Think?

According to Prof. Nagy, pontos is not only sea, it is a crossing, a dangerous crossing indeed. The word pontos already contains a dangerous crossing in it.

Is there an aggravated danger with oinops: the “wine-faced sea”? You have enough clues to make your decision.

What do you say? Join the Oinops Team in conversation here in the forum, Return to the Wine-Dark Sea Part II

Coming up next: Oinops and Oxen

Useful Links and Resources

- Using Perseus Digital Library, with Anna Krohn

- Investigating Greek words: A Quick Guide to Perseus with Illustrated Worked Examples

- Decoding Ancient Greek Dictionary Entries, with Joel Christensen

PDF Quick Guides with Worked Examples:

Further guides to be published shortly on this site: check out the Learn: Learning Modules page for these and other resources.

- An Introduction to Ancient Greek Meter

Notes

[1] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor.

[2] Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013