Following the exploration of Aphrodite and Artemis in the shorter Homeric Hymns, it’s Athena’s turn. There are two hymns: 11 and 28. I start with the shorter one:

Homeric Hymn (11) to Athena

[1] Of Pallas Athene, city-protector [erusi-ptolis], I begin to sing.

Terrible [deinos] is she, and with Ares she loves deeds of war [polemēios],

the sacking [perthesthai] of cities [polis] and the shouting [aütē] and wars [ptolemos].

It is she who protects [rhuesthai] the army as they go forth and come back.

[5] Hail-and-take-pleasure [khaire][1], goddess, and give us good fortune [tukhē] with happiness [eudaimoniē]!adapted from translation by H.G. Evelyn-White[2]

Εἲς Ἀθήναν

Παλλάδ᾽ Ἀθηναίην ἐρυσίπτολιν ἄρχομ᾽ ἀείδειν,

δεινήν, ᾗ σὺν Ἄρηι μέλει πολεμήια ἔργα

περθόμεναί τε πόληες ἀϋτή τε πτόλεμοί τε,

καί τ᾽ ἐρρύσατο λαὸν ἰόντα τε νισσόμενόν τε.

5 χαῖρε, θεά, δὸς δ᾽ ἄμμι τύχην εὐδαιμονίην τε.

What might have been the occasion on which this hymn was performed?

Allen and Sikes[3] note:

This … hymn ha[s] no formula of transition to a rhapsody. Hence it is very doubtful whether the hymn was a prelude at a recitation at Athens or elsewhere. The cult of Athena “πολιάς” [polias] or “πολιοῦχος” [polioukhos, “protecting a city”] was common to many Greek states (Farnell Cults i. p. 299).

So, whether or not it was the prelude to another story, I looked at the epithets and descriptions of Athena to see what else was going on.

The first epithet is Pallas. Pallas is frequently applied to Athena, or used alone to refer to her, so it is a generic, standing epithet. LSJ[4] notes that it is:

commonly derived from πάλλω [pallō, “brandish”], either as Brandisher of the spear, or παρὰ τὸ ἀναπεπάλθαι ἐκ τῆς κεφαλῆς τοῦ Διός [para to anapepalthai ek tēs kephalēs tou Dios, “having sprung up from the head of Zeus”], etc, but probably originally virgin, maiden.

The Oxford Classical Dictionary[5] provides a different origin for the name, based on two different stories in Apollodorus: “either from a playmate of the same name accidentally killed by the goddess (Apollodorus 3.12.3) or from a giant Pallas whom Athena overcame (ibid 1.6.2).” Both possibilities involve Athena killing, which ties in with her warlike aspect, and then taking on the name, maybe as a permanent reminder of her supremacy? Hesiod’s Theogony mentions a titan of that name:

Eurybia too, a goddess among goddesses, bore to Kreios, after union in love, huge Astraios, and Pallas, and Perses, who was transcendent in all knowledge.

Theogony 375–376[6]

But I have no other sources for LSJ’s suggestion of the name referring to her “maiden” aspect, so it is not clear how they arrived at it. There are other words used to refer to her unattached status anyway. I wonder if it could be the name of a previous goddess or perhaps the titan whose role was absorbed into that of Athena. What does anyone else think?

Also in line 1 is erusi-ptolis “guardian or protector of the city or cities”; ptolis is a variant of polis, “city.” If the Hymn was performed in connection with an occasion of some sort, the performers would perhaps have thought of Athena as one who protected their own city, even if it did not form a prelude to any other recitation. The term occurs here, in Hymn 28 (below), and at Iliad 6.305: Hecuba has gone into the storechamber and selected a robe [peplos]:

… the one that was the most beautiful in pattern-weavings [poikilmata] and the biggest, [295] and it shone like a star … 296 She went on her way, and the many highborn women hastened to follow her. 297 When these [women] had come to Athena’s temple at the top of the citadel, 298 Theano of the fair cheeks opened the door for them, …[300] she whom the Trojans had established to be priestess of the Athenian goddess. 301 With a cry of ololu! all lifted up their hands to Athena, 302 and Theano of the fair cheeks, taking up the peplos, laid it 303 along the knees of Athena the lovely-haired, and praying 304 she supplicated the daughter of powerful Zeus: [305] “O Lady Athena, city-protector [erusi-ptolis], shining among goddesses: 306 break the spear of Diomedes, and grant that the man be 307 hurled on his face in front of the Scaean Gates; so may we 308 instantly dedicate within your shrine twelve heifers, 309 yearlings, never broken, if only you will have pity [310] on the city of Troy, and the Trojan wives, and their innocent children.” Thus she prayed, but Pallas Athena granted not her prayer.

Iliad 6.296–311, adapted from Sourcebook[7]

This scene from the Iliad is reminiscent of the procession with a peplos that took place in Athens and which is depicted on the Parthenon frieze:

The Trojans are not able to get protection from Athena, because she is on the side of the Achaeans; as Hera says:

“… For of a truth we two, I and Pallas Athena, [315] have sworn full many a time before all the immortals, that never would we shield [alexein] Trojans from the day of destruction, not even when all Troy is burning in the flames that the warlike sons of the Achaeans shall kindle.”

Iliad 20.313–317, adapted from Sourcebook

Back to the Homeric Hymn 11: at the start of line 2 Athena is described as deinē, glossed in the H24H Core Vocabulary[8] as “awful, terrible, awesome,” and the rest of lines 2 and 3 focus on Athena’s warlike aspect, comparing her with Ares. Again this is reminiscent of scenes in the Iliad which is set during the Trojan War, and on several occasions we see Athena involved in the midst of battle.

In the Hymn, there are two terms relating to war: in line 2 the adjective polemēios, related to war,” and in line 3 ptolemos (equivalent to polemos, “war”). Also woven in are two forms of the word for city, again with and without the ‘t’: in line 1 we saw erusi-ptolis and in line 3 there is polis, associated here with the opposite, attacking form of war, perthesthai, “to sack.” Also in line 3 is aütē, “a cry, shout, especially battle-shout, war-cry.” All these terms in just two lines convey much of the tumult of battle and war.

In line 4 the focus returns to Athena in her role of protector during times of war: rhuesthai is related to eruein which we saw in the compound erusi-ptolis in line 1. Her protective aspect is mentioned as the people or army [laos] go out and come back, journeys which frame a war itself.

This is reminiscent of the Trojan War in epic: the ‘Catalogue of Ships’ (and of Trojans) in Iliad 2 lists all the forces and their leaders; other episodes of the Epic Cycle, the Nostoi, and the Odyssey cover the return, although not everyone makes it back safely; Athena is depicted as a helper of Odysseus, although not of the rest of his companions.

The final line of this short Hymn prays for good fortune and happiness, perhaps more in times of peace.

So could it have been a generic hymn that was used before and/or after war? Or in the hope of avoiding war? What do you think?

Homeric Hymn (28) to Athena

[1] I begin to sing of Pallas Athene, the glorious goddess,

with the looks-of-an-owl [glaukōpis], inventive [polumētis], implacable [a-meilikhos] of heart,

revered maiden [parthenos], city-protector [erusi-ptolis], strong-in-defence [alkēeis],

Tritogeneia. Wise [mētieta] Zeus himself bore her

[5] from his awful head arrayed in warlike [polemēion] arms

of beaming [pamphanoōn] gold, and awe [sebas] seized all the gods as they gazed.

But she, Athena, stood before Zeus who holds the aegis [aigiokhos] —

after springing quickly from his immortal head—

shaking a sharp spear [akōn]: great Olympus began to reel

[10] terribly [deinon] at the might of the goddess with the looks-of-an-owl [glaukōpis], and earth round about

cried fearfully, and the sea [pontos] was moved and tossed

with dark waves, while foam burst forth

suddenly: the bright Son of Hyperion stopped

his swift-footed horses a long while, until the maiden [kourē]

[15] had stripped the heavenly armor from her immortal shoulders,

she, Pallas Athena. And wise [mētieta] Zeus was glad.

And so hail-and-take-pleasure [khaire], daughter of Zeus who holds the aegis [aigiokhos]!

As for me, I will keep you in mind [memnēmai] along with the rest of the song.

adapted from translation by H.G. Evelyn-White[9], incorporating phrases from Gregory Nagy[10]

Εἲς Ἀθήναν

Παλλάδ᾽ Ἀθηναίην, κυδρὴν θεόν, ἄρχομ᾽ ἀείδειν

γλαυκῶπιν, πολύμητιν, ἀμείλιχον ἦτορ ἔχουσαν,

παρθένον αἰδοίην, ἐρυσίπτολιν, ἀλκήεσσαν,

Τριτογενῆ, τὴν αὐτὸς ἐγείνατο μητίετα Ζεὺς

5σεμνῆς ἐκ κεφαλῆς, πολεμήια τεύχε᾽ ἔχουσαν,

χρύσεα, παμφανόωντα: σέβας δ᾽ ἔχε πάντας ὁρῶντας

ἀθανάτους: ἣ δὲ πρόσθεν Διὸς αἰγιόχοιο

ἐσσυμένως ὤρουσεν ἀπ᾽ ἀθανάτοιο καρήνου,

σείσασ᾽ ὀξὺν ἄκοντα: μέγας δ᾽ ἐλελίζετ᾽ Ὄλυμπος

10δεινὸν ὑπὸ βρίμης γλαυκώπιδος: ἀμφὶ δὲ γαῖα

σμερδαλέον ἰάχησεν: ἐκινήθη δ᾽ ἄρα πόντος,

κύμασι πορφυρέοισι κυκώμενος: ἔκχυτο δ᾽ ἅλμη

ἐξαπίνης: στῆσεν δ᾽ Ὑπερίονος ἀγλαὸς υἱὸς

ἵππους ὠκύποδας δηρὸν χρόνον, εἰσότε κούρη

15εἵλετ᾽ ἀπ᾽ ἀθανάτων ὤμων θεοείκελα τεύχη

Παλλὰς Ἀθηναίη: γήθησε δὲ μητίετα Ζεύς.

καὶ σὺ μὲν οὕτω χαῖρε, Διὸς τέκος αἰγιόχοιο:

αὐτὰρ ἐγὼ καὶ σεῖο καὶ ἄλλης μνήσομ᾽ ἀοιδῆς.

This Hymn (28) to Athena is a little longer, 18 lines, and starts with just over three lines of epithets and characteristics.

The first line is identical to that of Hymn 11.

In line 2 there is glaukōpis, another epithet which occurs frequently in the Iliad (36 times) and Odyssey (57 times) as well as in Hesiodic poetry, and which is translated or explained in various different ways. LSJ and Autenrieth[11] gloss as “gleaming eyed,” Evelyn-White translated as “ bright-eyed”, and earlier translations sometimes have “gray-eyed,” related to glaukos “bluish green or gray,” while the Brill dictionary[12] has “with the face or eyes of an owl,” and Gregory Nagy and Leonard Muellner discuss this interpretation in an episode of the Reading Homeric Greek series[13], with “with the looks of an owl” referring to the two-way process of looking.

An association with owls is certainly made in Athens, where coins depict a type of owl, and the word glaux refers to the Little Owl.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Also in line 2 of the Hymn 28 is the epithet polumētis, familiar as a frequent epithet of Odysseus, particularly in the Odyssey, often when he speaks, but on other occasions as well. The term is glossed as “of many devices, crafty, shrewd,” which seems apt when applied to the trickster hero, although another option is “resourceful” when applied to Odysseus, or as “of many counsels” which is rather more neutral. The mētis part means “counsel, wisdom, plan, device.” In a Hymn addressed to Athena, perhaps the more positive aspects of this epithet are intended! Evelyn-White’s translation has “inventive” here. How would you translate it in this context?

Next in line 2 is the adjective ameilikhos, glossed in LSJ as “implacable, relentless”, and originally translated by Evelyn White as “unbending.” It occurs only a few times in the Homeric tradition, including at Iliad 9.158 where it is applied to Hades, Iliad 9.572 where it refers to a Fury (Erinys), and in Homeric Hymn (33) to the Dioscuri, where it refers to the sea [pontos] during a storm. So it seems ominous if not downright dangerous. In Hymn 11 we saw Athena described as deinē; here the phrase “implacable of heart” perhaps stands in for a similar idea.

In line 3, Athena is described as maiden or unmarried, parthenos, and she is celebrated in this aspect in the Parthenon in Athens. We already noted one of the special occasions with a peplos in procession. But she is not the only goddess to whom this attribute is applied: Artemis is another example, and Hestia in Homeric Hymn (5) to Aphrodite, line 28.

Continuing line 3 we see again the epithet erusi-ptolis, “city protector”, as in line 1 of Hymn 11.

The adjective alkēeis “courageous, valiant” occurs only here, but is related to the noun alkē, glossed in LSJ as “strength as displayed in action, prowess, courage; strength to avert danger, defence, help”. A goddess would probably not need to draw on courage in the way a mortal would in the face of danger or war, although prowess would be important. In Athena’s case the aspect of defence and averting danger seems more relevant and relates to that of being a “city defender”.

The final, generic, epithet at the start of line 4 is Tritogeneia, another with a disputed meaning and origin. LSJ says:

Trito-born, a name of Athena … (Variously explained in antiquity, from the lake Τριτωνίς [Tritōnis] in Libya, from which an old legend represents the goddess to have been born, E. Ion 872…; or from Triton, a torrent in Boeotia, Paus. 9.33.7, cf. Apollod. 1.3.6; or from a spring in Arcadia, Paus. 8.26.6; or from τριτώ [tritō, Aeol. word for κεφαλή [kephalē] (Sch. Ar. Nu. 985, Tz.ad Lyc. 519; Athamanian acc. to Nic. (Fr. 145) ap. Hsch.), i.e. head-born; or, born on the third day of the month, Ister 26 (the 23rd, τρίτῃ φθίνοντος, Sch.BT Il. 8.39); or, the third child after Apollo and Artemis, Suid. s.v. τριτογενής; or, as representing Nature, born thrice in the year, D.S. 1.12; or because she was author of the three main bonds of social life, Democr. 1b, 2.)

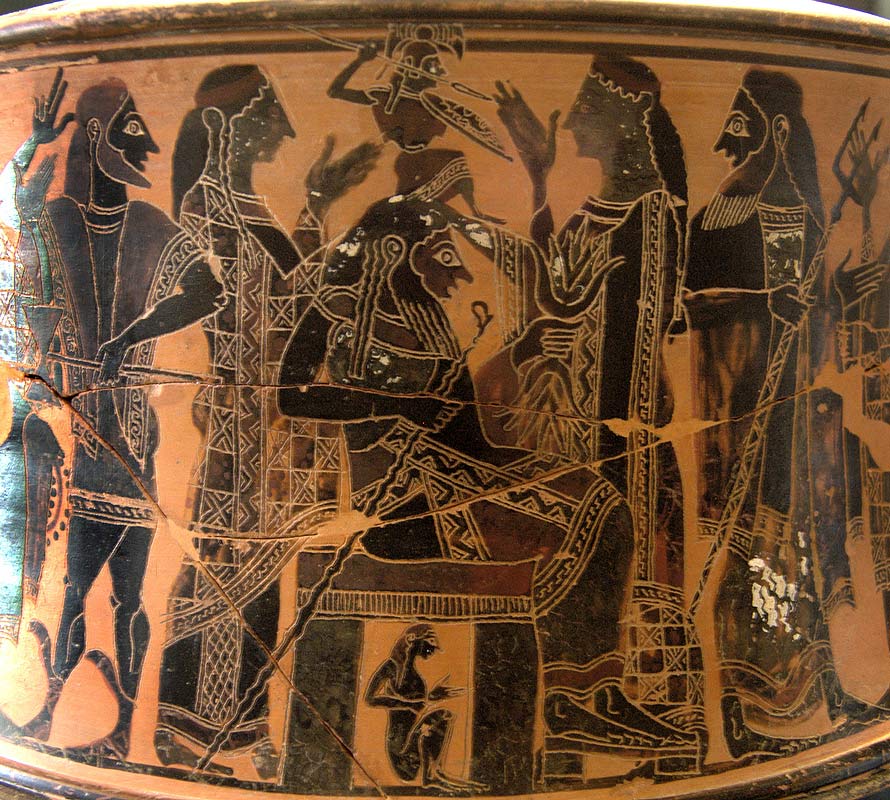

Lines 4–15 form a short narrative, describing the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus.

In Hymn 28 Athena was described in line 2 as polu-mētis; in line 4 Zeus has a related epithet, mētieta. LSJ glosses this as “counsellor” or “all-wise”. Since Athena emerges from Zeus’ head, it is not surprising that Athena shares this ability with him (even if the ancient Greeks did not necessarily conceive of the brain as being the seat of thinking).

However, the Hesiodic version of the story makes a more explicit link to Athena’s mother, Mētis:

Zeus, king of the gods, made Mētis first his wife; Mētis, most wise of deities as well as mortal men. But when at last she was about to give birth to Athena, goddess with-the-looks-of-an-owl [glaukōpis], then it was that having by deceit beguiled her mind 890 with flattering words, he placed her [Mētis] within his own belly by the advice of earth, and of starry Sky. For thus they persuaded him, lest other of ever-living gods should possess sovereign honor in the room of Zeus. For of her [Mētis] it was fated that wise children should be born: 895 first the glancing-eyed Tritonian maiden, having equal might and prudent counsel with her father…

Hesiodic Theogony 886–896, adapted from Sourcebook[14]

In Hymn 28, Zeus has the epithet aigiokhos, “aegis-bearing,” (from aigis and the verb ekhein], but in the Iliad it is Athena who wears and shakes the aegis:

…owl-vision [glaukōpis] Athena went among them holding [ekhein] her priceless aegis [aigis] that knows neither age nor death. From it there waved a hundred tassels of pure gold, all deftly plaited, and each one of them worth a hundred oxen. [450] With this she darted furiously everywhere among the masses of the Achaeans, urging them forward, and putting courage into the heart of each, so that he might fight and do battle without ceasing.

Iliad 2.446–452, adapted from Sourcebook[15]

In the narrative part of Hymn 28, it is striking that Athena’s spear-brandishing and warlike aspect affect Olympus and the sun above, and the earth and sea below (lines 9–15). So how much more dreadful would the effect be on mortals! The aegis is terrifying but also richly decorated with those golden tassels or fringes—although in artworks they are shown as intertwined snakes!—and Athena’s armor in the Hymn is of shining gold.

Athena first emerges fully armed, brandishing a spear, then removes her armor. The reverse process occurs in the Iliad when she prepares to join the fighting directly alongside Hera:

733 As for Athena, daughter [kourē] of Zeus who has the aegis [aigiokhos], 734 she let her woven robe [peplos] slip off at the threshold of her father, [735] her pattern-woven [poikilos] peplos, the one that she herself made and worked on with her own hands. 736 And, putting on the tunic [khitōn] of Zeus the gatherer of clouds, 737 with armor she armed herself to go to war, which brings tears. 738 Over her shoulders she threw the aegis, with fringes on it, 739—terrifying [deinē]—garlanded all around by Fear personified. [740] On it [= the aegis] are Strife [Eris], Resistance [Alkē], and the chilling Shout [Iōkē, as shouted by victorious pursuers]. 741 On it also is the head of the Gorgon, the terrible [deinos] monster, 742 a thing of terror [deinē] and horror, the portent [teras] of Zeus who has the aegis [aigiokhos]. 743 On her head she put the helmet, with a horn on each side and with four bosses, 744 golden, adorned with pictures showing the warriors [pruleis] of a hundred cities [polis]. [745] Into the fiery chariot with her feet she stepped, and she took hold of the spear [enkhos], 746 heavy, huge, massive. With it she subdues the battle-rows of men— 747 heroes against whom she is angry, she of the mighty father.

Iliad 5.733–747, adapted from Sourcebook[16]

The adjective deinos / deinē, “terrible,” occurs three times in this passage in the description of the aegis and the Gorgon; we also saw this word in Hymn 11 to describe Athena herself (line 2), and in Hymn 28 it is used adverbially to describe the trembling of Olympus (line 10). Here the aegis is described as a portent of Zeus who is again given the epithet aigiokhos, so there seems to be a very close connection between Zeus, Athena, and the aegis.

In the Iliad Athena is on the side of the Achaeans, but they represent a group of cities. She might not be defending those cities, but she is heartening and strengthening the fighting men. So not only does she provide defensive strength, but offensive strength.

Her defensive aspect is illustrated on a much smaller scale when she protects Achilles from Hector’s attack:

He hurled his spear as he spoke, but Athena breathed upon it, [440] and though she breathed but very lightly she turned it back from going towards renowned Achilles, so that it returned to glorious Hector and lay at his feet in front of him.

Iliad 20.438–441, Sourcebook[17]

This seems to me to be a much less terrifying, but effective, aspect of Athena’s role in war and defense.

In Hymn 28 I noticed a partial nested ring composition, with Athena described as “Pallas” in lines 1 and 16, as parthenos, “virgin”, in line 3 and kourē, “maiden”, in line 14, overlapping with the descriptions of Zeus as mētieta, “wise,” in lines 4 and 16 and as aigiokhos, “aegis-bearing,” in lines 7 and 17. This last epithet, however, is part of the closing sequence, the transitional wording which Gregory Nagy (2011)[18] describes as a metabasis:

Metabasis is a device that signals a shift from the subject of the god with whom the song started—what I have been calling the hymnic subject—and then proceeds to a different subject—in what must remain notionally the same song. Ideally, the shift from subject to different subject will be smooth. Ideally, the different subject will be consequential, so that the consequent of what was started in the humnos may remain part of the humnos. This way, the transition will lead seamlessly to what is being called ‘the rest of the song’.

So what might the subject of “the rest of the song” have been with Hymn 28? What kind of themes do you think are suggested? Are there any stories or myths associated with Athena that you think might fit well, if you were the rhapsode performing?

Join me in the Forum to share your ideas and impressions!

Related topics

Divine Deceiver: Hermes in the Homeric Hymns

Selected vocabulary

Definitions based on LSJ[19] and Autenrieth[20]

aigíokhos [αἰγίοχος, αἰγίοχον] adj. “aegis-holding” (epithet of Zeus)

aigís [αἰγίς , αἰγίδος, ἡ] “aegis,” described in Autenrieth as: “(originally emblematic of the ‘storm-cloud,’ cf. ἐπαιγίζω): the aegis, a terrific shield borne by Zeus, or at his command by Apollo or by Athena, to excite tempests and spread dismay among men; the handiwork of Hephaestus; adorned with a hundred golden tassels, and surmounted by the Gorgon’s head and other figures of horror”

akōn [ἄκων, ἄκοντος, ὁ] “javelin, dart, smaller and lighter than ἔγχος [énkhos]”

aléxein [ἀλέξειν] “to ward off, avert; defend”

alkē [ἀλκή, ἀλκῆς, ἡ] “defense, defensive strength, valor”

alkēeis [ἀλκήεις, ἀλκήεσσα, ἀλκήεν] adj. “valiant, courageous, warlike, strong in defense”

a-meílikhos [ἀμείλιχος, ἀμείλιχον] adj. “implacable, harsh, stern, relentless”

aütē [ἀυτή, ἀϋτῆς, ἡ] “a cry, shout, especially battle-shout, war-cry”

deinós [δεινός, δεινή, δεινόν] adj. “dreadful, fearful, terrible”

énkhos [ἔγχος, ἔγχεος, τό] “spear, lance” (the long spear)

erúein [ἐρύειν] “to draw, drag, mid., draw for oneself or to oneself, rescue, esp. the fallen in battle”

erusí-ptolis [ἐρυσί-πτολις, ὁ, ἡ] “city-rescuing, city-protecting, epithet of Athēna” (Autenrieth) from ptólis/pólis “city,” and erúein “draw, drag; rescue”

eudaimoníā / eudaimoníē [εὐδαιμονίη / εὐδαιμονία, εὐδαιμονίας, ἡ] “prosperity, good fortune; happiness”

glaukōpis [γλαυκῶπις, γλαυκώιδος, ἡ] “gleaming-eyed” (Autenrieth), “with the looks of an owl” (Gregory Nagy)

glaúx [γλαύξ, γλαυκός, ἡ] “the little owl”

hálmē [ἅλμη, ἅλμης, ἡ] “sea-water, brine”. Usually a medium associated with Poseidon, who is so often Athena’s rival.

khaírein [χαίρειν] “to be glad, joyful, rejoice; hail or farewell”

kourē / kórē [κούρη / κόρη , ἡ] “girl, maiden, daughter”

mētiéta / mētiétēs [μητίετα / μητιέτης, ὁ] “counsellor, ‘all-wise'”, epithet of Zeus

Pallás [Παλλάς, Παλλάδος, ἡ] “Pallas”, epithet of Athena

pállein [πάλλειν] “to brandish, swing”

pamphanóōn [παμφανόων, παμφανόωσα] participle “bright-shining, beaming” (refers to armor or the sun)

parthénos [παρθένος, παρθένου, ἡ] “maiden, virgin, girl”

péplos [πέπλος, πέπλου, ὁ] “robe, woven cloth”

pérthein / pérthesthai [πέρθεσθαι] “to sack, plunder, lay waste, regularly of cities”

polemḗios [πολεμήιος, πολεμήιον] adj. “of or pertainint to war or battle, warlike”

polúmētis [πολύ-μητις, πολυμήτιος, ὁ, ἡ ] “of many devices, crafty, shrewd,” an epithet also used of Odysseus.

ptólemos / pólemos [πτόλεμος / πόλεμος, πολέμου, ὁ] “war”

ptólis / pólis [πτόλις / πόλις , πόλιος, πόληος] “city”

rhústhai / rhúesthai [ῥύεσθαι] “to draw to oneself, i. e. draw out of danger, to rescue, save, deliver; to shield, guard, protect” — variant middle form of erúein

sébas [σέβας, τό] “reverential awe”

túkhē [τύχη, τύχῃς, ἡ] “good fortune, luck”

Notes

1 Gregory Nagy has formulated this for khaire which occurs in many of the Homeric Hymns: “Now, at this precise moment, with all this said, I greet you, god (or gods) presiding over the festive occasion, calling on you to show favor [kharis] in return for the beauty and the pleasure of this, my performance.” In translations he uses a more manageable “Hail-and-take-pleasure.”

From “The earliest phases in the reception of the Homeric Hymns.” p. 328. Electronic version of the printed version published 2011 in The Homeric Hymns: Interpretative Essays (edited by Andrew Faulkner) 280–333, Oxford University Press.

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

2 Greek and English text:

The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Homeric Hymns. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

Online at Perseus

3 Allen & Sikes: The Homeric Hymns, edited, with preface, apparatus criticus, notes, and appendices. Thomas W. Allen. E. E. Sikes. London. Macmillan. 1904.

Online at Perseus

4 Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940.

Online at Perseus

5 The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Edited by Simon Hornblower, Antony Spawforth & Esther Eidinow. Fourth edition, 2012. Oxford. Entry for “Pallas,” p.1070.

6 Hesiodic Theogony. 1–115 Translated by Gregory Nagy, 116–1022 Translated by J. Banks and adapted by Gregory Nagy.

Online in the Kosmos Society Text Library

7 Sourcebook: Gregory Nagy, editor: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, v15, 2020.

Online in the Kosmos Society Text Library

Homeric Iliad: Samuel Butler’s translation, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray.

Online in the Kosmos Society Text Library

Greek text: Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920.

Online at Perseus

8 Core Vocabulary of key Greek terms from The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours.

Online at Kosmos Society

9 Greek and English text:

The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Homeric Hymns. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

Online at Perseus

10 I have incorporated the translation of Gregory Nagy for the final line, which also occurs in many of the hymns: “But as for me, I will keep you in mind [memnēmai] along with the rest of the song.” in “The earliest phases in the reception of the Homeric Hymns.” p. 328.

11 Georg Autenrieth. A Homeric Dictionary for Schools and Colleges. New York. Harper and Brothers. 1891.

Online at Perseus

12 Montanari, Franco. The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek. English edition edited by Madeleine Goh & Chad Schhroeder. Brill, Leiden and Boston. 2015.

13 Homeric Greek | Odyssey 1.44–62: Athena, Odysseus, and longing for home, video discussion online at Kosmos Society

14 Hesiodic Theogony, 1–115 Translated by Gregory Nagy, 116–1022 Translated by J. Banks and adapted by Gregory Nagy.

Online in the Kosmos Society Text Library

Greek text: Hesiod. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. “Theogony”. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

Online at Perseus

15 Homeric Iliad: Samuel Butler’s translation, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray.

Online in the Kosmos Society Text Library

Greek text: Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920.

Online at Perseus

16 Homeric Iliad: Samuel Butler’s translation, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray.

Online in the Kosmos Society Text Library

Greek text: Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920.

Online at Perseus

17 Homeric Iliad: Samuel Butler’s translation, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray.

Online in the Kosmos Society Text Library

18 Nagy, Gregory. “The earliest phases in the reception of the Homeric Hymns,” retrieved from an electronic version of the printed version published 2011 in The Homeric Hymns: Interpretative Essays (edited by Andrew Faulkner) 280–333, Oxford University Press. 2011. p.329.

Article available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

19 Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940.

Online at Perseus

20 Georg Autenrieth. A Homeric Dictionary for Schools and Colleges. New York. Harper and Brothers. 1891.

Online at Perseus

Texts retrieved September 2023 and February 2024

Image credits

Athena, called ‘Athena Cherchel-Ostia’

Photo: Kelvin Chen, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license, via Flickr

Goddess Athena

Photo: Vassilis, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, via Flickr

Detail from Peplos scene, from Block V, east frieze of the Parthenon, c 447–433 BCE

Photo: Twospoonfuls, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, via Wikimedia Commons

Athena Promachos, tondo of Attic type B kylix, c 500–490 BCE

Photo: © Marie-Lan Nguyen, Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license, via Wikimedia Commons

Bust of Athena, “Velletri Pallas” type, 2nd century CE copy of original by Kresilas c 530–420 BCE

Photo: Bibi Saint-Pol, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

New style silver tetradrachm coin of Athens, 86–84 BCE

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Temari 09: Athena, Guardian of the Sacred Temple

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license, via Flickr

Birth of Athena, Attic exaleiptron (black-figured tripod), c 570–560 BCE

Photo: Bibi Saint-Pol, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Detail from Athena fighting, Acropolis Museum

Photo: Ricardo André Frantz (Tetraktys), Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons

Statue of Athena, Roman 1st century CE, copy of Greek original mid-5th century BCE by Myron

Photo: Carole Raddato, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, via Flickr

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by galleries or museums, or on Wikimedia Commons or Flickr, at the time of publication on this website.

Images retrieved January–February 2024

___

Sarah Scott is a member of Kosmos Society